African American Queen of the Road

Bessie Stringfield: Tales of the Road Queen and Me ( Part 2)

By Ann Ferrar

The original stories of Bessie Stringfield, African American motorcycling pioneer, were written in the 1990s by Ann Ferrar, an author, friend and protégé of Bessie. Ferrar's narratives shed light on Bessie's hidden talents and achievements in the pre-Civil Rights era, sparking global admiration for Bessie that exists to this day. In PART 2 of this retrospective, Ferrar looks at the two different Americas each woman saw. Ferrar's coming book is the biography "African American Queen of the Road: Bessie Stringfield: A Woman's Journey Through Race, Faith, Resilience and the Road." The book contains details of Bessie's life known only to Bessie and Ann.

© Copyright 1990-2024, Ann Ferrar. Ann Ferrar reserves all rights to this content and to her earlier stories of Bessie Stringfield, upon which this content is based. Library of Congress Copyright Registration Numbers TXu-2-160-705; TXu-2-088-760, et al. WGA Registration I338479, et al. These narratives, written by the author with her expression of thought and other original, primary-sourced story elements, are protected against theft by copyright and intellectual property laws. This material and Ferrar's other stories on Bessie Stringfield are NOT in the public domain for unauthorized use by other parties. Strictly prohibited are adaptations and other derivative, imitative works in any media or format, non-fiction or fiction. Please respect the author's rights and the wishes of Bessie Stringfield.

Bessie Stringfield and Me

One Road, Two Women, Two Different Americas

By Ann Ferrar

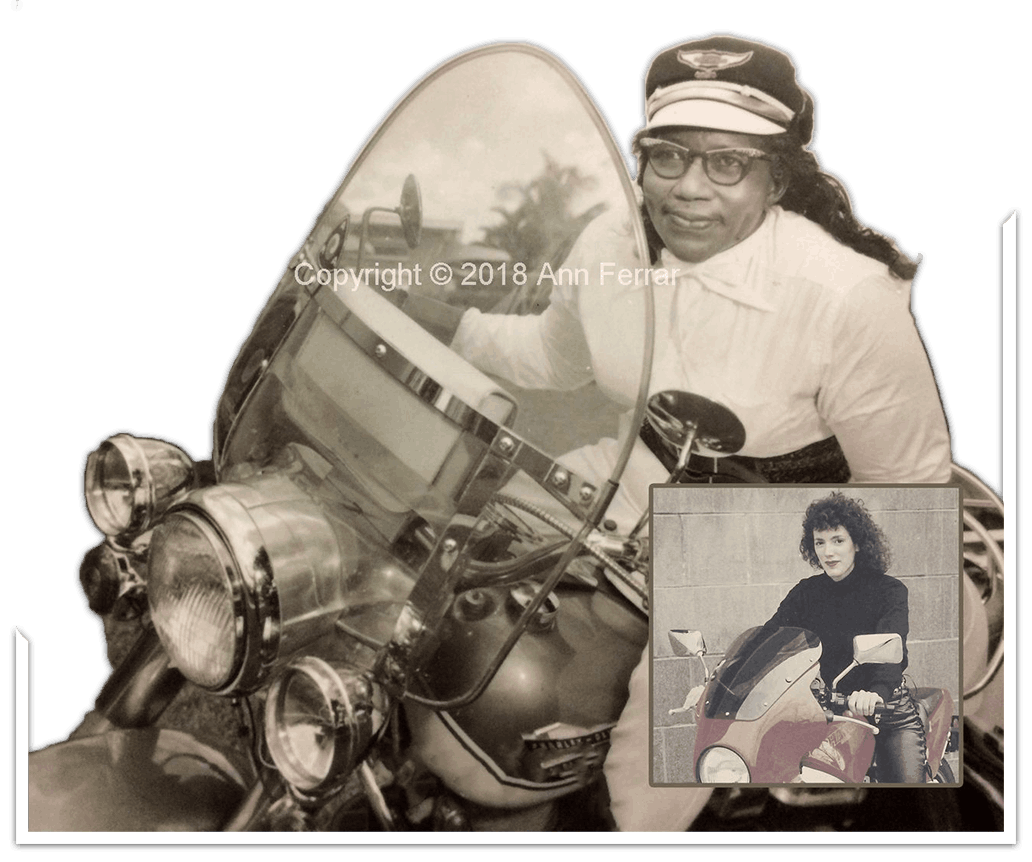

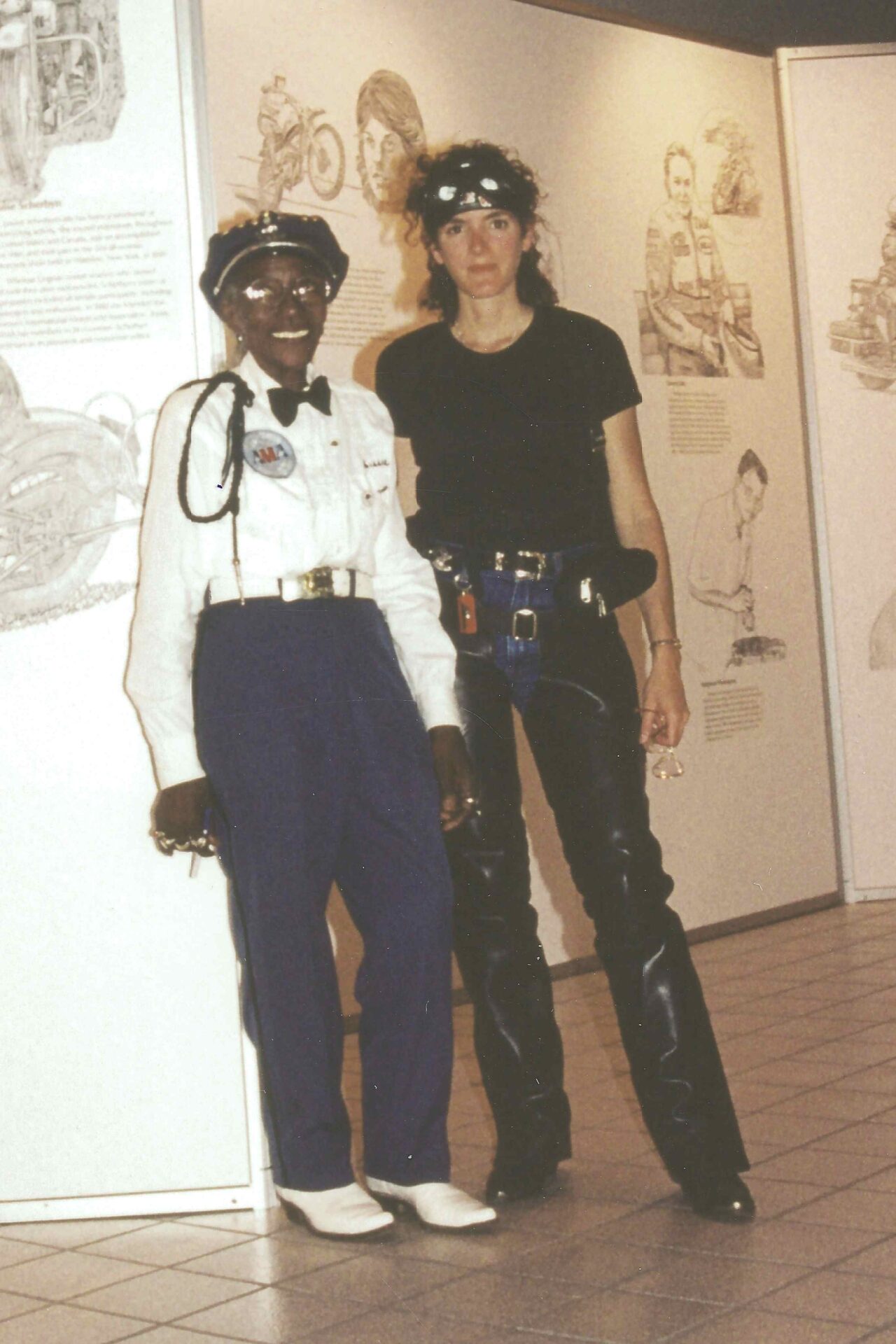

The first time I encountered Bessie Stringfield, we were visiting the American Motorcycle Heritage Museum in Ohio. That was in 1990, when Bessie was 79. For me, meeting Bessie Stringfield was like a jolt of electricity, as when you touch something dormant that you didn't realize was statically charged. At age 35, I was more than four decades younger than her. As a journalist and life-long student of women's history in the 20th century, I recognized the elder Bessie Stringfield not as a light that had dimmed, but rather as a daring woman of color who had risen above racial and gender barriers in the pre-Civil Rights era.

Yet Bessie Stringfield, born in 1911, had been overlooked despite her achievements in Jim Crow America. No one had taken enough notice to even view her in that light. There was no archival evidence because Bessie had carved her own path before society was ready. There was no movement of Black women who followed her on motorcycles during her lifetime. So, Bessie Stringfield was never a public figure among the masses. Rather, she was a solo, hidden figure.

Back then as a female rider myself, I loved that Bessie had used her talent and nerve to go against type from an unusual vantage point: the saddles of the 27 Harley-Davidson motorcycles she owned in her lifetime, plus the Indian Scout that was her first bike. In my original stories of Bessie Stringfield, the first of which was the 1993 tribute article in American Iron, I wrote of how despite the risks, Bessie had taken eight solo long-distance rides, or "gypsy tours," around the United States. She racked up about a million miles over her 60-year riding career.

Women just didn't embark on such escapades in her era, yet there was Bessie Stringfield, riding the roads quietly as a hidden figure. I wrote about how Bessie earned her spot as a civilian courier, or dispatch rider, on the home-front during the Second World War. In my stories I described how Bessie trained rigorously alongside Black men. She was the only woman in a small unit in the segregated army of the 1940s. I described a technique peculiar to the pre-interstate era: how to weave a makeshift bridge with tree limbs and rope to get a motorcycle across a shallow swamp, though she never had to do this in the line of duty. I wrote stories of how Bessie, with a borrowed military crest on her own Harley, traversed America's rough roads to carry documents and mail in her saddlebags among domestic bases.

I could see that Bessie Stringfield’s story would be lost upon her death, so I was determined to prevent that loss. Bessie knew she had a legacy to leave and that I was an accomplished writer of narrative non-fiction. We had mutual trust and respect for each other. So, Bessie told me all about her life. She was finally ready to sit down and reflect back on her private life and events she had lived through.

The most prescient thing I did was record Bessie on audio tape with her permission and encouragement, during the last three years of her life. It took a while for me to gather her tales, interpret and piece them together, since Bessie did not reminisce in a linear manner. My copyrighted stories are the only authentic, primary-sourced stories on the full spectrum of Bessie Stringfield's life. Due to the vagaries of the internet, here I must reiterate that my material on Bessie Stringfield is not in the public domain for unauthorized use by other parties. (If you've read any of these stories elsewhere but my name was not referenced as the source, you were reading a pirated or plagiarized piece. Ditto for pieces in other media, including podcasts and videos, as well as web encyclopedias that lack citations of my bylined works.)

I always believed there was another facet of Bessie's hidden life that cried out to be told. My readers needed to know what a talented and daring motorcycle rider Bessie Stringfield had been in a milieu that was largely male and white. My description of her brief foray into motordrome riding was one piece of it; her founding and leading an all-male motorcycle club in Miami was another. In my stories I also described how Bessie was subjected to gender bias when she donned a disguise to compete amongst men in a dirt-track race: Bessie won the gritty heat but was denied the prize when she took off her helmet.

In my eyes, that helmet was Bessie's metaphorical crown, hence the title of my coming book, African American Queen of the Road: Bessie Stringfield—A Woman's Journey Through Race, Faith, Resilience and the Road. The book is her definitive biography, containing details of her private life known only to Bessie and me.

In the 1950s, Bessie bought a house in a mostly Black community in Miami-Dade, Florida, where she would spend the rest of her life. Bessie gave me the rare privilege of visiting her at home. I was born in Brooklyn, New York, a late baby boomer who was a college student in the 1970s at the height of the women's movement. I benefited from the feisty women who had paved the way for me to go against type. So, I viewed Bessie in a different light than did her peers in the local community.

I viewed and wrote of Bessie Stringfield as an undiscovered feminist who had predated the modern women's movement. Yet when I met her, Bessie Stringfield was unknown to the larger public and overlooked even by women's and African American historians. I knew that Bessie—who was in the shadows as many elderly women are—had lived an amazing life. But nobody's ears except mine were attuned to what this tiny, unassuming elder had to say. It was the start of a fascinating, ongoing conversation and friendship between us that lasted until her passing in 1993. Some of Bessie's closest peers, who are now deceased, shared their memories with me as well.

On my own motorcycles I, too, rode tens of thousands of miles alone, with nothing but the drone of the wind and the engine inside my full-face helmet. Often I phoned Bessie from spartan motel rooms in the evenings during the first three years of my road trips for the original edition of my first book, Hear Me Roar: Women, Motorcycles and the Rapture of the Road. Bessie enjoyed hearing of my adventures and travails on the road and giving me advice. I told her about the diverse women riders I met from across the continent. She enjoyed hearing about the colorful rallies I attended and the motorcycle field games at which I excelled. Bessie certainly never ran out of tales from her six decades of riding. We shared stories with doses of humor and our calls always ended with a prayer for our mutual health and safety. In her frail but spirited voice, Bessie liked to sing her favorite hymn, Precious Lord, Take My Hand.

While Bessie Stringfield and I were both talented, long-distance riders who shared the same feelings of exhilaration astride our bikes, many of our road experiences were worlds apart. For starters, we rode during different eras with different societal norms based on skin color and gender expectations, to name just two. Bessie and I traded stories of her experiences as a Black Southern woman on a persnickety Harley in a segregated era, and mine as a white woman from the Northeast, zooming along the asphalt slabs of America on a high-tech bike. I rode on paved roads and had my pick of motels and diners. I was alone, but not alone in society as Bessie could be when trying to find access even to life's bare necessities in the Jim Crow South.

Unlike Bessie Stringfield, throughout my journeys I was never denied lodging, gas or a restaurant meal. Never did I have to ride my mechanically sound bike on a creepy back road as the only route available to avoid the Klan. Never did I have to swerve around beer cans deliberately tossed in my path by rednecks. And unlike Bessie, I was never stalked by a bigot in a pickup truck who ran me off the road, wrecking my bike and scraping me up. This unnerving incident, which I wrote about in my early stories about Bessie, has struck a chord among African American readers today. They point out, and rightly so, that our society has not made nearly enough progress in the decades since Bessie was forced off her bike due to racial profiling. Unless you've been living under a rock and are oblivious to current events, we all know how true that is.

© Copyright-protected material

© Copyright-protected material

I asked Bessie how she got through the tough times and how she felt about the people who harbored ill intent toward her. Bessie Stringfield did not need to ponder the answer. "I knew Jesus Christ and I know Him now," she said. "Those men did not know Jesus Christ. He was always with me. They couldn't see Him, but I felt Him. Oh, I was tested a few times to find the good in some people. In the end, no matter what happens in our lives, it's got to be about love. That is the final conclusion you must always try to attain."

Bessie Stringfield spoke those words to me 30 years ago. Clearly, her courage was multi-layered. She showed as much bravery in keeping her faith, capacity to love, and an ability to bond with unlikely people even when faced with prejudice. From listening to her for three years, I surmised that Bessie's life was not defined by struggle or rebellion, but rather in how she reacted to each situation and each individual. That was Bessie's true superpower. She knew that anger and resentment would make her weaker, not stronger. Yet in search engines today, I see reductive pieces on Bessie that draw on my work but ignore this vital part of her character. To ignore it is to miss the essence, the truth, and the point of Bessie Stringfield.

original pictures that Bessie gifted to biographer Ann Ferrar during their friendship. Photo must not be used by other parties without prior written permission from Ms. Ferrar.

Bessie's expansive outlook enabled her to experience many positive, life-affirming encounters with people of all races in her 60 years of riding around America. Bessie met locals who were curious and friendly, and white gas station owners who were impressed at her "nerve," as she put it. Some—even in the South—were so taken with Bessie Stringfield that they filled her tanks for free.

I asked her about this several times, to be sure I was hearing her straight, to be sure she wasn't softening the fabric of white society or Jim Crow racism for my sake. Speaking in the colloquial language of her era, in a recorded interview Bessie assured me, "All along the way, wherever I rode, the people were overwhelmed to see a Negro woman riding a motorcycle." Bessie reiterated this sentiment in different ways during our ongoing conversations, in which Bessie looked back on the sum total of her life.

Still, Bessie told me that in the South, she had to look over her shoulder. “If you had Black skin, you couldn’t get a place to stay,” she said into my tape recorder, adding, “I slept with people’s children a lot because no one would rent me a motel room.” I wrote of how sometimes, Bessie slept on her bike at gas stations, using her rolled-up jacket as a pillow across the handlebars, while resting her feet on the rear fender. Bessie gave me photos of herself stretched across her bike and a collection of other vintage pictures, including original negatives and contact sheets. In the photo on this web page, Bessie Stringfield is vamping for the camera, but alone on the road, finding a place to spend the night was a serious matter.

I asked her, "Weren't you afraid, being so alone and vulnerable out there?"

"I was not alone," she replied. "When I get on the motorcycle I put the Man Upstairs on the front. I'm very happy on two wheels." Bessie often spoke to me of her riding days in the present tense, even though a chronic heart condition had kept her off motorcycles for several years already.

_________

"I recognized the elder Bessie Stringfield

not as a light that had dimmed, but rather as a daring

woman of color who had risen above racial and

gender barriers in the pre-Civil Rights era.”

—Ann Ferrar

_________

Today, people have asked me if Bessie Stringfield used the Green Book, the mid-20th-century guide for Black motorists. It popped back into the nation's consciousness when the movie of the same name hit theaters in 2018. It is a myth that Bessie always relied on the Green Book. She began traveling well before the first edition came out in 1936 and before a lot of Black-friendly motels were in business. There weren't always lodgings near her routes. And not all innkeepers approved of an unescorted woman doing something so far afield from what was expected of her. So I can tell you that lots of times, Bessie Stringfield relied on her faithful unseen companion, the Man Upstairs.

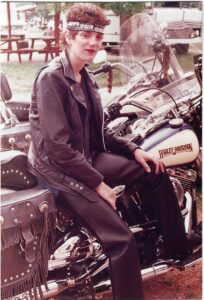

As for my own solo adventures on two wheels, with dogged persistence and a motorcycle safety course, I grew into an assertive urban rider and a long-distance motorcyclist in my own right. I rode for 18 years on six different bikes, covering 35 of the lower 48 states and parts of Canada. Bessie enjoyed shooting the breeze with me about riding, especially since her male cronies from her old Iron Horse Motorcycle Club had disappeared from her life long ago.

When Bessie and I began our legacy project, I was living in an apartment in TriBeCa on the lower west side of Manhattan. My motorcycle was parked in the lot beneath my building, but it was never parked for long, since I took many long-distance rides to do on-location work for Hear Me Roar. That is how I met Bessie.

I wrote first drafts of Bessie's 1993 American Iron tribute, and my narrative story “Bessie B. Stringfield: The Color Blue” for Hear Me Roar, using my low-tech pens on legal pads. I scrawled in old-fashioned longhand while drinking coffee at Socrates, my favorite Greek diner. Often I sat in a window booth, with my Honda Hawk GT650 on the sidewalk within my line of sight. I have always felt that facing the first blank page with longhand is an intimate way to begin writing. Since my friendship with Bessie was personal, it was the perfect marriage of words and experience. One man in my circle of Manhattan riding buddies nicknamed me the Literary Biker Chick. I told Bessie that in a sense, we were a pair of literary biker chicks, her part being oral and mine being written. I was blessed to be an actual part of Bessie's later life—to be a genuine part of her story as it is known throughout the world today.

This points to why Bessie Stringfield's life story and my stories about Bessie Stringfield's life are inseparable. They are the literary equivalent of conjoined twins who cannot be pulled apart, which is why, as noted earlier, they are not in the public domain for unauthorized use by other parties. They are original works that I created from scratch. A good analogy is that Bessie Stringfield is like a heroine in a novel, in that Bessie could not, and would not, exist in the hearts and minds of an international audience today if one author had never written that novel. (Put formally in the parlance of literary law, my stories of Bessie Stringfield are my intellectual property.)

Socially and culturally significant figures sometimes take their place in history only after enough time has passed to enable appreciation and recognition. That is the case with Bessie Stringfield. My early narratives about Bessie's hidden achievements were ahead of the curve when I wrote them in the 1990s. Bessie Stringfield left her mark on humanity for her bravery, determination and grace in the face of prejudice based on race and gender. I was the writer and respectful friend who noticed—and who worked patiently with the elderly woman to capture her memories before it was too late. Bessie Stringfield has a legacy for her courage and achievements against society's odds. I did not let her slip into obscurity. That is my legacy. — Ann Ferrar

Author-biker Ann Ferrar at Sturgis, South Dakota,

August 1990. During that same road trip,

Ann met Bessie Stringfield for the first time.

Photo by Becky Brown, Founder, Women in the Wind.